Edwin Shuker

“Baghdad was the centre of the Jewish world for over 1,500 years. My ancestors wrote the Talmud, the Babylonian Talmud. They invested so much in Iraq … I can’t live with the fact that my grandfather is buried here and that we’ve abandoned him and we are just saying Goodbye Baghdad… Goodbye everything, and we no longer even look back…”

At the opening of the documentary, Edwin leaves his family behind in safe suburban North London, prepared to risk his life to rekindle a Jewish presence in the country of his birth. In 1951, when most of the Jews fled to Israel, Edwin’s parents remained and continued to live a comfortable happy life. But like gamblers, he says, they overplayed their hand. In 1971 he and his family were fortunate to escape from Saddam Hussein’s regime with their lives.

Now it is perilous for everyone and Edwin’s childhood home in Baghdad’s Battaween district is in a particularly dangerous part of the city. But Edwin is determined to keep his connection to the place alive.

He has decided to buy a house in Iraq. It will be in Erbil, the capital of the Kurdish area in the North East corner of the country. The Islamic State frontier is just a short drive away. But Edwin dreams that one day, just maybe, in 30, 40, 50 or 60 years’ time, the Jews of Iraq will be able to reconnect with their ancestral birthplace. If he doesn’t see this dream in his lifetime, at least he will know he set it in motion.

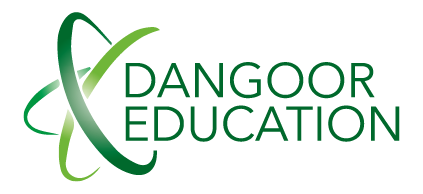

DAVID DANGOOR

“Iraq is still in our blood, in our bones. It’s like a distant bell ringing in the back of our heads, always reminding us where we came from.”

David was born in 1948, the same year that Israel was created. The new Israeli state marked the beginning of the end for Jews in Iraq. The Jewish community was plunged into crisis and instability, but nevertheless the Dangoors believed that the atmosphere would improve. The family had close Muslim friends, contacts in government, a good life – they felt secure. They seemed to have the best of everything. For 25 years they had been at the centre of an exciting nation-building period when Baghdad was transformed from a sleepy Ottoman city into the commercial hub of a British-dominated, oil driven new country. David’s mother was crowned the first ever “Miss Baghdad”.

David grew up secure and happy in his grandfather’s villa by the Tigris. Business was booming. His family attended fancy parties and rubbed shoulders with the royal family and government ministers. They could not imagine that their lifestyle would come to an end. But in 1958 the British-installed monarchy was overthrown, and their confidence was crushed. David’s parents finally made the decision to leave Iraq. They were among the last to get out without risking their lives.

EILEEN KHALASTCHY

David Dangoor’s aunt

“Jews, Moslems and Christians, we [were] all Iraqis. It was a good time... I still miss Baghdad.”

In 1974 Eileen was among the last few hundred Jews to flee Baghdad, leaving just 280 behind. She had seen the country through British rule, independence, revolutions, war with Israel and persecution under the Ba’ath Party.

As a child, Eileen’s life in Baghdad was idyllic. She misses it still and stayed in Iraq as long as she could. The first sign of change was when the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem moved into the house next door to her home. In 1941 she was too young to understand the reason for the sudden acid attack on her on the riverbank of the Tigris, that the politics of Palestine/Israel and the influence of the Nazis was behind the frightening change of atmosphere in Baghdad. But anger over the British re-conquest of Iraq and the partition of Palestine was building up and it soon led to violent attacks against the Jews in Baghdad.

Eileen and her family ignored all opportunities to leave until suddenly, it was almost too late. By the late 1960s, their lives were in danger, their passports withdrawn; and two or three families were escaping every week. Nevertheless, today she remembers the good times, always smiling.

DAVID KHALASTCHI

Eileen Khalastchy’s cousin-in-law

“No difference between Muslims, Jewish, Christian and all the minorities. Iraq for all Iraqis.”

Ninety-year-old David’s love of horses goes back to his childhood growing up in the countryside two hours south of Babylon. He still canters on his grey mare. Life took off for the Khalastchis after the British arrived in Iraq. His father was one of the few people who spoke English and thanks to strong relationships with the local tribes, the family were central to the development of agriculture in the area south of Baghdad.

By the late fifties, Iraq was swept up in a consumer revolution. David owned a car dealership selling large American cars. He expected financial ruin after the revolution of 1958, but instead, there was big demand from the new embassies representing Russia, China and Eastern interests. David had the best five years of his life. He paints an exuberant picture of his life in Baghdad, his Muslim friends, the fun they had and his sadness at having to leave in March 1967. He managed to get out when thousands of Jews were trapped without passports. Within three months the tension in the Middle East would develop into the Six Day War.

ESPERANCE BEN-MOSHE

“We were frightened to death. I was all night hearing the noises, the shouts in the air.... some iron falling, doors were breaking, people were shouting.”

Esperance was an impressionable young girl who hid on the roof with her family during the terrifying riot of 1941, Baghdad's Kristallnacht. Later, as the Jewish community started to organise their departure, she was delighted by the picnics and mysterious expeditions to the desert to learn Hebrew in the secret schools run by Zionists. Her family were not Zionists, but in an atmosphere of panic, they joined the airlift of 1951 when virtually the whole community was taken from Iraq to Israel. They fled with £10 in their pockets. Today she lives in Tel Aviv.

SALIM FATTAL

“The Jews did not understand what happened. Arab nationalists in Iraq, with the Mufti and the influence of the Nazis during the thirties, they are in danger. The Jews are in danger.”

Broadcaster and writer Salim Fattal, who lives outside Jerusalem, pioneered Israel’s Arabic language radio and television. He was born in Baghdad during British rule, after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and before independence in 1932. His childhood in a poor neighbourhood of Baghdad was scarred by the murder of his uncle during ugly anti-Jewish riots in 1941. Nonetheless, he grew up identifying as equally with Jews as with the Arab communities around him.

In the late 1940s Salim joined a mixed community of communists. They campaigned to rid the country of the puppet regime installed by the British and to take back Iraqi oil from British operators. After the creation of Israel, Communism and Zionism both became capital offences and Salim fled to Israel, more out of fear of being punished as a communist than for a commitment to Zionism.

DANNY DALLAL

“You had this feeling that all eyes were upon you all the time. We can’t afford to look like Jewish kids out on the street. So in the street we start speaking Muslim.”

Danny’s father was the director of a company that imported tyres from Japan. His uncle – whom he loved dearly – owned a chocolate factory. The family lived the high life, mixing with Jews and Muslims at members’ clubs established by the British for the elite, with tennis courts and cocktail bars.

But by the late 1960s the Jewish community was isolated and was thought to be harbouring a “fifth column” acting for Israel. People started disappearing; a few at a time, or in small groups, they vanished from their families. His uncle was arrested in the middle of the night. Six months later a notice in the paper announced that he had been found guilty of spying, and he was hanged.

DAVID SHAMASH

David Dangoor’s neighbour

“The [Second World] War hardly touched them. There were parties every night. The community was living in a bubble. They were not touched by the Holocaust and they were living as if there was no war and nothing has happened much.”

David Shamash is David Dangoor’s neighbour in London, as he was in Baghdad when they were children. Part of a prominent Baghdadi family, David’s father became an Iraqi MP. Ministers would visit the Shamash home to have dinner and play cards. But after the Suez Crisis in 1956, there was a sense of anxiety bubbling under the surface of this easy-going life. After 1969 it was only the action of old friends in high places that protected the family from arrest and the trials that saw many members of the Jewish community hanged. In 1970, after years of living under threat, David’s mother decided it was time for the family to escape over the mountains to Iran.

ELI AMIR

“I long for Baghdad, for the river there, my Baghdad.”

Iraqi-born Eli has written several autobiographical novels about the conflicted Jewish community in Baghdad, loving their country but at times terrified for their lives. Eli’s mother’s best friend was their Arab neighbour. The two women breast-fed each other’s children. This woman would later protect the family and save their lives.

Eli still misses the smells and sounds of Baghdad, but feels that there was no choice but to flee Iraq in the poisonous atmosphere that followed the creation of Israel. And now there was a country that welcomed them. The family left for the newly-created Israel in the airlift of 1951 and Eli now lives on the outskirts of Jerusalem. He became political advisor to the government on Arab affairs in the sixties.

FREDDY KHALASTCHY

Eileen Khalastchy’s son

"My parents stayed on. They didn't think they did anything wrong."

Freddy Khalastchy was a child when the British-installed monarchy was overthrown in 1958. His parents decided to continue living in Baghdad under the new left-wing military leader, Abdul Karim Kassem. The political project seemed benign, and favoured a multi-cultural Iraq. Freddy’s parents were happy at home. But after the Ba'ath Party took over in the first of a series of coups in 1963, Jewish passports were withdrawn and Iraq lurched towards a sectarian, militarised system. Now they were trapped. The Israeli victory in the Six Day War of 1967 had immediate and deadly consequences for the Jews of Baghdad. From then on life was dominated by news of arrests and trials; it was about trying to survive without being noticed.

ZVOOLOON HARELI

“Some said: we will be communists, we'll change the regime and then it will be better for the Jews. We said: No. We need to do everything we can to leave and get to Israel.”

Zvooloon was only 15 when he joined the Zionist underground movement in Iraq. It was here that he learnt to speak Hebrew and helped to organise the emigration of thousands of Iraqi Jews to Palestine, before it became Israel. Zvooloon was trained to use arms so he could defend the district he was responsible for, and became secretary of the educational department of the Baghdad branch. In 1949, he smuggled himself out of Iraq and he now lives near Tel Aviv.